The term “Lack of Moral Fibre” was introduced into RAF

vocabulary in April 1940 and was ‘designed to stigmatize aircrew who refused to

fly without a medical reason.’ [1] While it is now most

commonly associated with ‘shell-shocked’ bomber crews, in fact aircrew from all

commands could be and were categorized as LMF in the course of the war. Humiliating

as the concept was, the myths about the treatment of LMF were more terrifying

than the facts.

The RAF entered the war confident that its volunteer aircrew,

all viewed as the finest human material available, would not suffer from any

crisis in morale. Yet already by January 1940, attrition rates of over 50% in

Bomber Command, triggered a crisis in confidence among commanders and crews. At

the same time, Coastal Command morale was undermined by unreliable engines and

unarmed aircraft that proved extremely vulnerable to Luftwaffe attack.

On March 21, 1940 the Air Member for Personnel met with senior

RAF commanders to develop a procedure for dealing with flying personnel who refused

to ‘face operational risks.’ The concern of these senior officers was that the

refusal to fly would become more widespread, debilitating the RAF. The RAF’s dilemma

was that flying was ‘voluntary,’ hence the refusal to fly was not technically a

breach of the military code.

The RAF needed an alternative means of punishing and deterring

refusals to fly on the part of trained aircrew. Furthermore, because of the

on-going crisis, the procedures for dealing with the problem were required immediately.

There was no time for lengthy study into the causes or best practices for

treatment. Over time the polices on LMF were modified significantly and

increasingly discredited. Yet it is telling that at the height of the Battle of

Britain, AVM Sir Keith Park strongly advocated the policy, emphasizing that aircrew

deemed LMF should ‘be removed immediately from the precincts of the squadron or

station.’[i]

Furthermore, while nowadays LMF is most commonly associated

with bomber crews, the statistics show a that only one third of LMF cases came

from Bomber Command. Surprisingly, fully a third came from Training Command, while

both Coastal and Fighter Commands also had their share of LMF cases. Fighter

Ace Air Commodore Al Deere describes in detail a case of a pilot from No 54

Squadron who avoided combat and was later ejected from the squadron for being “yellow.”[ii]

Fighter Ace Wing Commander Bob Doe records another incident towards the end of

the Battle of Battle of Britain in which a Squadron Leader conspicuously avoided

combat, but because the Squadron Leader was from a different squadron, no

action was taken.[iii]

For the men who continued flying operations, the fate of

those ‘expeditiously’ posted away from a squadron for LMF was largely shrouded

in mystery. Legends about LMF abound. During the war itself, it was widely believed

that aircrew found LMF were humiliated, demoted, court-martialed, and dishonorably

discharged. There were rumors of former aircrew being transferred to the

infantry, sent to work in the mines, and forced to do demeaning tasks. Aircrew expected to have their records and

discharge papers stamped “LMF” or “W” (for Waverer) with implications for their

post-war employment opportunities.

Long before the war was over, however, the very concept of

LMF was harshly criticized and increasingly discredited. In the post-war era,

popular perceptions conflated LMF with “shell shock” in the First World War and

with the more modern concept/diagnosis of Post Traumatic Shock

Disorder/Syndrome PTSD/S. In literature — from Len Deighton’s Bomber to Joseph

Heller’s Catch 22 — aircrew were increasingly depicted as victims of a

cruel war machine making excessive and senseless demands upon the helpless

airmen. Doubts about the overall efficacy of strategic bombing, horror stories depicting

the effects of terror bombing on civilians, and general pacifism in the

post-war era have all contributed to these cliches.

In reality, LMF was a more complex and nuanced issue. First,

although there are documented instances of aircrew being humiliated in a parade

during which flying and rank badges were stripped off, such public ceremonies

were extremely rare. The vast majority of references to such public spectacles are

second hand; that is, the witness heard about such procedures at a different

station or squadron. Historical analysis of the records, on the other hand,

show almost no evidence of widespread humiliation. Furthermore, over the course of the war, less than one percent of aircrew were posted

LMF, and of these the vast majority were partially or completely

rehabilitated. Only a tiny fraction were

actually designated LMF or the equivalent. (The term used for describing

aircrew deemed cowardly varied over time, including the terms “waverer” and

“lack of confidence.”) Furthermore, the process for determining whether aircrew

were LMF or not was far more humane than the myths of immediate and public

humiliation suggest.

While the decision to remove a member of aircrew from a unit

was an executive decision, applied when member of aircrew had “lost the

confidence of his commanding officer,” the subsequent treatment was largely

medical/psychiatric. Thus, while a Squadron Leader or Station Commander was

authorized — and expected! — to remove any officer or airman who endangered the

lives or undermined the morale of others by his attitude or behavior, a man

found LMF at squadron level was not automatically treated as such by the RAF

medical establishment.

On the contrary, RAF medical personnel were at pains to

point out that LMF was not a medical diagnosis at all! It was a term invented

by senior RAF commanders in order to deal with a phenomenon they observed — and

feared. In consequence, once a man had

been posted away from his active unit, he found himself inside the medical

establishment that employed Not Yet Diagnosed Nervous (NYDN) centers to examine and

to a lesser extent treat individuals who had “lost the confidence of their

commanding officers.”

The medical and psychiatric officers at the NYDN centers (of

which there were no less than 12) were at pains to understand the causes of any

breakdown. They did not assume the men sent to them were inherently malingerers

or cowards. On the contrary, as a result of their work they made a major

contribution to understanding — and helping the RAF leadership to understand —

the causes for a beak-down in morale. These included not only inadequate

periods of rest, but irresponsible leadership, lack of confidence in aircraft,

and issues of group cohesion and integration. As a result of their interviews

with air crew that had been posted LMF, for example, the medical professionals

were able to convince Bombing Command to reduce the number of missions per

tour and to exempt aircrew on second tours from the LMF

procedures altogether.

Meanwhile, more than 30% of the aircrew referred to NYDNs

returned to full operational flying (35% in 1942 and 32% in 1943-1945), another

5-7% returned to limited flying duties, and between 55% and 60% were assigned

to ground duties. Less than 2% were completely discharged.

In addition, there is considerable circumstantial evidence that

at the unit level, pains were taken to avoid the stigma of “LMF.” No one

understood the stresses of combat better than those who were subjected to them.

It was the comrades and commanders, who were themselves flying

operationally, who recognized both the symptoms and understood the consequences of flying stress.

These men largely sympathized with those who were seen to have done

their part. Certainly, men on a second tour of

operations were treated substantially differently — at both operational units

and at NYDNs — than men still in training or at the start of their first tour.

Fighter Ace Air Commodore Al Deere, DSO, OBE, DFC and Bar posed

the dilemma as follows: “The question ‘when does a man lack the moral courage

for battle?’ poses a tricky problem and one that has never been satisfactorily solved.

There are so many intangibles; if he funks once, will he next time? How many

men in similar circumstances would react in exactly the same way? And so on.

There can be no definite yardstick, each case must be judged on its merits as

each set of circumstances will differ.”[iv] (Photo below courtesy of Chris Goss)

While conditions varied over time, from station to station, and

from commander to commander, on the whole RAF flying personnel did not seek to

punish or humiliate a comrade who in the past had pulled his weight. Instead,

informal means of dealing with cases of men who “got the twitch” — other than

posting them LFM — were practiced. Precisely because such practices were

“informal” they are almost impossible to quantify, yet the specific cases

documented are almost certainly only the tip of the iceberg.

This is not to say that LMF policies did not have a powerful

impact on RAF culture. The fact that so many aircrew knew about LMF and had

heard rumors of humiliating practices for dealing with LMF demonstrates that the

possibility of being designated LMF was an ominous reality to aircrews. Because of the

draconian punishment expected based on the myths surrounding LMF, the threat of

being designated LMF acted as a deterrent to willful or casual malingering. Tragically,

the threat of humiliation may also have pushed some men to keep flying when

they had already passed their breaking point, leading to errors, accidents, and

loss of life.

Deere noted: “In my first tour [during the height of the

Battle of Britain], despite the many narrow escapes I was always confident that

I could come through alright. In contrast, throughout [a later tour], although

it was far less hectic, there was always uppermost in my mind the thought that

I would be killed….I don’t think I was any more frightened than previously, and

it can only be that I had returned to operations too soon after so many nerve-racking

experiences…. The result was a lack of confidence, not so much in my ability to

meet the enemy on equal terms, but in myself (or my luck).”[v]

He admitted that by the time he was relieved of his command and sent on a publicity

tour to the United States he was, in fact, overdue for another rest.

During the Second World War, psychiatric professionals increasingly

came to recognize that “courage was akin to a bank account. Each action reduced

a man’s reserves and because rest periods never fully replenished all that was

spent, eventually all would run into deficit. To punish or shame an individual

who had exhausted his courage over an extended period of combat was increasingly

regarded as unethical and detrimental to the general military culture.”[vi]

Yet we should not forget that behind the notion of LMF was

the deeply embedded belief that courage was the ultimate manly virtue and that

a man who lacked courage was inferior to the man who had it. RAF aircrew were

all volunteers. They were viewed and treated as an elite. Membership in any

elite is always dependent on the fulfilment of certain criteria. Since the age

of the Iliad courage has been — and remains — the most fundamental

characteristic expected of military elites around the world. And it probably

always will be.

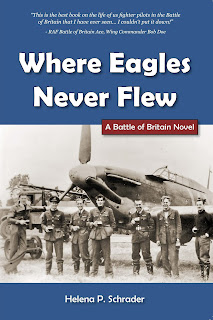

A case of LMF is highlighted in and

contributes pivotally to the plot of “Where Eagles Never Flew.” You can see a video teaser of "Eagles" at: Where Eagles Never Flew Video

Buy now!

direct from Itasca or from Barnes and Noble

Buy on Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk

[1] Edgar Jones, “LMF:

The Use of Psychiatric Stigma in the Royal Air Force during the Second World

War,” The Journal of Military history 70 (April 2006). 439

[i]

Jones, 446.

[ii]

Deere, Alan C. Nine Lives. Crecy Publishing. 1959. 111-119.

[iii]

Doe, Bob. Fighter Pilot. CCB Aviation Books, 2004. 44.