Every author has their own, unique voice which develops naturally in the course of writing, but when characters speak -- particularly characters in a historical setting -- they should not sound like the author but like themselves. What this means is that characters in a historical novel must use language that is appropriate to their age, education level, family background and profession -- and of course the time period in which they lived.

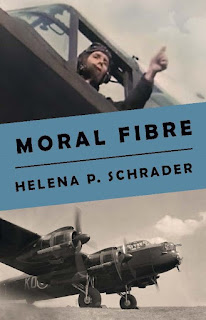

The greater challenge is when writing, as with Moral Fibre, a book set in a modern -- but not contemporary -- English-speaking environment. No, people in the Second World War did not ask "what's up?" They didn't say "awesome" to express approval or "I hear you" to mean they sympathize. They certainly didn't fill their sentences with "like" every fourth word. They had a variety of other expressions which were popular. And that's the trick.

It is much easier avoiding something inappropriate than becoming sufficiently comfortable with language we no longer use to employ it fluently and without making the characters sound stilted. The RAF was notorious for using jargon that even their contemporaries found nearly incomprehensible. They used phrases like "buying it" and "going for six" to mean getting shot down. "Brassed off" and "cheesed off" referred to being fed up with something. A "gong" was a medal, a "fruit salad" a lot of medals, a Mae West a life vest and a "prang" an accident. Smashed, sozzled, pie-eyed, pissed, and pickled were all ways of saying drunk, while "corkers," "crumpets," "streamlined piece," and "bird" were all other words for "popsie" or woman/girl. To "pancake" was to land, to "bind" was to complain, to "get the drift" was to understand, to "hold the can" was to be responsible, to "kip" was to sleep, to "shoot a line" was to brag or boast. Fortunately, there are dictionaries of RAFese available to the interested historian! I have included one at the back of Moral Fibre.

I was also fortunate to have access to a large number of primary sources written during or shortly after the war. These still employed the contemporary idiom. Accounts written by RAF personnel use their jargon unpretentiously and in context. After reading enough, the language of the period became not only comprehensible but seeped into my own vocabulary and I felt "fluent" in it.

Here's an example of a character speaking RAFese that I wrote without having to think about it.

“It was sheer chaos and confusion from the moment I pancaked in London. You remember the letter. I thought I was meeting up with a very streamlined piece of nice called Cynthia, but she showed up with her friend Julia, and of course I didn’t want to be rude. So, I called a friend of mine to see if he wanted to join us. We went to school together, but he’s flying a desk with the Admiralty after being wounded in the Med. He graciously agreed to join us — only to start charming Cynthia clear out of her knickers. All right, I don’t know if he got that far, but I was more than a little browned off! But there was Julia, and while she isn’t the corker Cynthia is, she wasn’t entirely humid. In fact, she was a terrific dancer, one thing led to another, and…” Adrian downed the whisky in a single swig and announced he needed another, looking around for an orderly.

“Don’t leave me in suspense! And what?”

“I think I got myself engaged.”

An issue that I found particularly challenging and never fully solved, on the other hand, was the correct use of expletives. Words that are now used casually by men (and even women) were much more taboo eighty years ago. To put these words in my character's mouths would have degraded them -- and yet, using the language of the time does not convey to modern readers the emotion behind such swear words. I did my best but I'm not sure I succeeded. Here's an example.

“I’m not fighting for no British Empire!” Nigel countered angrily. “I don’t give a tinker’s damn about the flaming British Empire. And if we’re fighting for democracy, then we need more of it right here in England! But I won’t never forgive the effing Nazis for what they’ve already done neither!”

Next week I will explore the message or theme of the novel.

Riding the icy, moonlit sky— They took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were less than fifty percent. Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one Lancaster skipper, his crew,and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to them all.

Flying Officer Kit Moran has earned his pilot’s wings, but the greatest challenges still lie ahead: crewing up and returning to operations. Things aren’t made easier by the fact that while still a flight engineer, he was posted LMF (Lacking in Moral Fibre) for refusing to fly after a raid on Berlin that killed his best friend and skipper. Nor does it help that he is in love with his dead friend’s fiancé, who is not yet ready to become romantically involved again.

No comments:

Post a Comment