As I have argued

elsewhere, after AVM Park the AOC of Eleven Group, the greatest burden in the Battle of Britain

fell not on the individual, young pilots but on the squadron and flight

commanders who led them. One of those was Wilfrid “Wilf” Clouston. He deserves to be remembered -- and not just for his role in the Battle of Britain.

(Shown below with his wife Anne Hyde.)

Clouston was born in Devonport, Auckland 15 January 1916. He was educated in Wellington, NZ, and started his working life as clerk at Woolworths. However, like many young men of his generation, he wanted to fly. Clouston concluded that the best route to a flying career was to join the RAF, which at the time (1936) was offering a limited number of short service commissions to young men from the Dominions. The competition for these few posts was fierce, and applicants were required to already have an “A” pilot’s license. Clouston, therefore, conscientiously obtained a license in New Zealand. Given the thousands of applications, however, it speaks for Clouston’s character and reputation that he was accepted — albeit provisionally. First, he had to prove he could fly to the satisfaction of the RAF by reporting to England to pass a civil flying test.

Clouston opted to work his way to England aboard a steamer bound for Southampton. Once in the UK, he passed the civil flying exam and then started to learn to fly the RAF way. In June 1937, he was promoted to (Acting) Pilot Officer and posted to No 19 Squadron at Duxford. This was the first RAF squadron to be equipped with Spitfires, which they received at the end of 1938. As a result, the pilots on No 19 Squadron were particularly familiar with and adept at handling the Spitfire — something that contributed to a higher survival rate among the core pilots.

Clouston was promoted to (acting) Flight Lieutenant before the shooting war started and fought throughout the Battle of Britain in this rank. He was awarded the DFC for his contribution to defending the skies over Dunkirk. The official citation read:

“During recent operations over France and Belgium, Flight Lieutenant Clouston shot down four enemy aircraft. He led his flight with determination and vigour and has shown great personal gallantry.” (Source: The Times announcement of the DFC)

In his letters home, Clouston allowed no trace of doubt about the outcome — or hint of the exhaustion and the stress under which RAF fighter pilots fought — to surface. He maintained a rigid façade of indomitable keenness. For example, in a letter to his parents in August 1940 he wrote:

Every time we run into them now, the odds are at least ten to one against us, but such is the spirit and the feeling over here that we don’t mind. … You can’t imagine the limits that this spirit rises to. I have had to order pilots on my flight to go on leave when they were due for it but refused, as they might lose an opportunity to have another crack at the ‘schweinehund.’” (Source: “Wilf: Wilfrid Grenville Clouston” by Richard Clouston).

In November, Clouston was promoted to Squadron Leader and posted to command 258 Squadron, which was composed predominantly of New Zealanders, or “Kiwis” as they called themselves. He had survived the Battle of Britain and was in an excellent position to pass on his knowledge to others. Up to this point, his career paralleled that of the majority of pre-war RAF fighter pilots, the men who formed the backbone of Fighter Command, enabling it to keep fighting — and drinking and laughing — despite the odds.

However, in the summer of 1941 Clouston’s career took a dramatic turn that ultimately led him to a different destiny — one that deserves far more recognition than is commonly awarded. On August 22, Clouston was appointed to command a newly formed New Zealand Air Force Squadron 488. Clouston had to forgo a promotion to Wing Commander to take this assignment, and he was also required to go to Singapore to join up with the squadron. He arrived in mid-September 1941, ahead of the squadron coming up from New Zealand. His flight commanders joined him at the end of September but it was October before the bulk of the squadron arrived from New Zealand. To Clouston’s dismay the squadron was outfitted not with Spitfires or even Hurricanes but with Brewster Buffalos.

In very little time, Clouston made an operational squadron out of the raw material sent him, but on 23 January 1942, he was posted to Operational Headquarters in Singapore. The exact sequence of what happened next is no longer clear, but Clouston appears to have been instrumental in ensuring that the ground crew and staff of 488 Squadron were aboard the MV Empire Star one of the last ships to depart Singapore before it fell to the Japanese. He, along with other RAF headquarter staff, destroyed any unserviceable aircraft still in Singapore. On 15 February 1942, the day Singapore surrendered to the Japanese, Clouston with a number of other senior RAF officers attempted to evade capture aboard an air-sea rescue launch. The following day, this launch was bombed and sunk by the Japanese. Clouston was among the survivors picked up by two small steamers. These, however, were in turn intercepted by the Japanese navy and told to sail to Sumatra. From here they were transferred to a Japanese POW camp at Palembang-Mulo.

In August 1942, Clouston refused to sign a “no-escape” clause and was therefore sent to a “higher security” (read: more inhumane) POW camp at Chueng Hwa. There he remained until he and other officers were transferred to Changi Jail in Singapore in January 1945. This transfer was presumably for ease of execution since the Japanese had standing orders dating from 1 August 1944 authorizing subordinate commanders to murder all officer prisoners, if the military situation warranted it. On August 16, a day after the unconditional surrender of Japan, the prisoners took over the running of Changi, but it was not until Allied troops (and supplies) could be parachuted to Singapore that conditions could significantly improve. It was officially 13 September 1945 before Clouston was freed and could start his journey “home” — in this case to his wife, and the son he had never met, in England. He arrived there 8 October 1945.

His wife Anne had been notified in April 1942 that her husband was “missing” but it was not until October of that year that she learned that he was alive but a POW. In three and a half years of imprisonment, Clouston was allowed to send only four postcards of 25 words each. He did not receive any mail until the first Red Cross package arrived in February 1944, two years after he was taken captive.

Between his capture and his release lay three and a half years of brutal treatment in inhumane conditions and near starvation. Clouston refused to live in the (marginally) better officer’s camp and insisted on working alongside the RAF personnel of “other ranks” imprisoned with him. Because the Japanese believed that their troops were too “honorable” to surrender, they held anyone who had allowed himself to be taken prisoner in contempt. Cultural attitudes and official policy combined to ensure that POWs were consciously and intentionally humiliated and degraded.

Rations were inadequate and declined progressively as the military situation for the Japanese deteriorated. Accommodations were overcrowded, unsanitary, and rat-infested. Medicine and medical equipment were effectively non-existent. The Japanese also refused to issue clothing, and neither bedding nor mosquito nets were provided. Yet prisoners were expected to carry out heavy labor such as building runways, loading and off-loading ships etc. for up to fourteen hours a day in the tropical heat. In consequence of all these factors POWs of the Japanese faced a casualty rate of 27%.

Needless to say, Clouston was not flying, not getting promoted, and not winning new “gongs” during those three and a half years. Yet that does not mean that he was not serving his country and not contributing to the defeat of a terrible tyranny. On the contrary, under the most adverse conditions imaginable, Clouston demonstrated courage, responsibility and compassion to an exceptional degree. His dedication to his men in adversity was impressive not only in military but in human terms. The Senior British Officer at Cheung Hwa Camp Wg/Cdr Willis-Sandford reported:

“S/L Clouston DFC, S/L Howell DFC, F/Lt J Goold, F/Lt TR Lamb, F/Lt RC Moore.

I wish to bring the names of the above mentioned officers to the notice of the appropriate authority. Their generous and untiring efforts on the behalf of the other ranks were most praiseworthy.”

It is unclear who the “appropriate authority” might have been and in any case the war was over. Clouston found himself still a Squadron Leader, a reservist whose Short Service Commission had expired in the middle of the Battle of Britain and competing for a permanent commission against men who had had the good fortune not to be taken prisoner of war. It is to his credit that he was given a permanent commission.

Over the next ten years, Clouston continued in active service with the RAF serving as Station Commander at RAF Turnhouse, RAF Tangmere, RAF Khormaksar, Aden, and RAF Northolt. He also served in the Air Ministry and at HQ Fighter Command, as well as attending the Joint Services Staff College. There is every indication that he could have reached senior rank, if his health had not intervened.

A brain tumor was diagnosed, but surgery failed and radiation treatment caused collateral damage. He was forced to retire from active service and returned to New Zealand with the expectation of living at most a year. He took up sheep farming and lived for twenty.

I wish to thank his son Richard Clouston for providing the materials for this short biography and reviewing it for accuracy.

My novels about the RAF in WWII are intended as tributes to the men in the air and on the ground that made a victory in Europe against fascism possible.

Lack of Moral Fibre, A Stranger in the Mirror and A Rose in November can be purchased individually in ebook format, or in a collection under the title Grounded Eagles in ebook or paperback. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

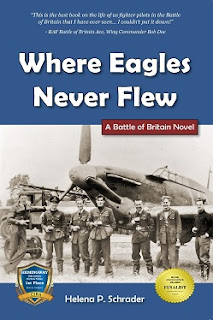

Where Eagles Never Flew was the the winner of a Hemmingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

wonderful story thank you

ReplyDelete