Sidney “Stevie” Stevens achieved brief fame in the UK in 2017 as one of the last surviving Lancaster pilots — and because of his story struck a chord in the British public in part because his wife of more than 70 years was part of his wartime story. Yet he was in many ways more representative of than exceptional in his generation. He exemplifies many features of what it meant to fly for the RAF in WWII.

Yet what appeals to me most is that Stevie — like Wilf — was not just a “war hero” but a man with skills more suited to peace.

Stevie was born poor — on December

14, 1921. His father worked for the Railway and his mother in a factory, and

Stevie (then still known as Sid) started his first job at the age of eight,

delivering goods for the local grocer. But life wasn’t all bad. Stevie belonged

to a choir and joined the Boy Scouts. Meanwhile, his father was determined that

he would get a better, cleaner job that the one he had and encouraged Stevie to

be good at school. This paid off in a scholarship to a grammar school in the

larger town of Bideford. He commuted the eight miles daily, walking two and

half miles each way, and covering the remaining distance by rail; because of

the train schedule, he was rarely home at night before six pm — often cold and

wet.

In 1933, Stevie’s family moved to

London, where his father had a better job as an engineer on electrical

locomotives. Stevie was allowed to transfer to the Henry Thorton grammar school

in Clapham Common, where (he says) some of the students were “fairly posh, but

not too posh.” At fifteen, he obtained

his school leaving certificate with commendable results and would have liked to

continue in the sixth form — but his father could not afford to keep him in

school. It was time to start “earning his keep.”

With good recommendations, Stevie

landed an office job in the Estates, Housing and Valuations Department at

Croydon in 1937 earning 17 shillings and 6 pence (less than a pound) a week.

Already convinced a war was inevitable, in 1938 Stevie tried to join the RAF

Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) but was turned down because he didn’t have the right

accent; the RAF preferred “public school types.” So he joined the Air Raid

Precautions (ARP) Service instead. He was on duty the night his own house suffered

a direct hit during the Blitz. His parents and an uncle, who had stopped by for

a cup of tea had all survived in the shelter, but Stevie lost everything he

owned except the clothes he was wearing.

Stevie later claimed:

“I looked up at the empty sky and said to myself: ‘You bastards, what a bloody awful thing to do, I’ll get my own back on you for this.’ I knew straight away I wanted to be a bomber pilot; not many people wanted to fly bombers, but I knew that I did and I was determined that I would.”

In April 1941, Stevie again applied to the RAFVR and was accepted as an “Aircraftman” and mustered for pilot training — after he’d completed the induction process and, of course, survived six weeks of “square bashing” learning to salute and march, while also receiving instruction in morse code, theory of flight and navigation, aircraft recognition and more. Stevie remembers the course as “demanding” and failure meant “remustering” for a trade other than pilot. At the end of six weeks, only 60% passed. Further training, including clay pigeon shooting, followed. It was October 1941 before Stevie arrived in Carlisle for “Elementary Flying Training” and his first ever flight in an aeroplane. One month later, Stevie was among the lucky candidates not to be “washed out” and could proceed with pilot training.

To Stevie’s astonishment, he was slated for training in the United States. Mid-December he was aboard the SS Bergensfjord found for Halifax along with hundreds of other aspiring pilots on their way to training establishments in Canada as well as the U.S. At Halifax they were taken to a central “dispersal unit” for assignments. Here, even in the middle of the Canadian winter, Stevie enthused about the quality of the accommodations, the abundance of food and the lack of black-out. In early January, Stevie proceeded to “No 2 British Flying Training School” in Lancaster, California. Despite it’s designation as a “British Flying Training School,” the school, “War Eagle School,” was a civilian flying school established under the U.S. government Civilian Pilot Training Program. All the instructors were civilians, although RAF personnel had administrative and disciplinary responsibility for the RAF trainees, and an RAF flying instructor did the final testing of candidates.

From February to August 1942, Stevie

advanced steadily through the various challenges of Primary and Advanced Flying

training, including night flying, instrument flying, cross-country navigation,

aerobatics and more. On 4 August, Stevie received his “wings,” symbolizing his

qualification as an RAF pilot. Yet Stevie’s letters of this period talk as much

(if not more) about the lavish hospitality he enjoyed from Americans. He was

invited into people’s homes, taken sailing and riding, given tours, introduced

to celebrities, and enjoyed the chaste company of nice American girls charmed

by him (and his accent, no doubt!). He describes barbeques and scrimp

cocktails, swimming parties in private pools and swimming in the Pacific, horse

shows, films and shooting. He tells of a host with a private airplane that

allowed the (not yet qualified British cadets!) to fly back to their airfield,

when it looked like they might be late on weekend. He would never live so well

again!

At the latest, when Stevie boarded

the Queen Mary in her grim wartime camouflage paint and wartime fittings

as a troop transport, reality started to set in again. He arrived back in

England on September 11 1942 and less than two weeks later had his first flight

in a twin-engine aircraft as part of his next stage of training. In October he

was sent to an Operational Training Unit (OTU) to start learning to fly

operational aircraft, in this case the Wellington. It was here that he “crewed

up” with a navigator, bomb aimer, wireless operator and rear gunner. Six months

later, the entire crew advanced to the Heavy Conversion Unit (HCU) where a

Flight Engineer and a mid-upper gunner joined them. At the end of them month,

they were posted to an operational squadron, No 57 at RAF Scrampton. Stevie

started his operational tour as a Sergeant Pilot.

1 May and 20 October 1943, Stevie flew

a total of 31 operations. Targets

included: Duisberg, Dortmund, Duesseldorf, Bochum (2x), Cologne (3x), Krefeld,

Gelsenkirchen, Hamburg (2x), Manheim (2x), Nuremburg (2x), Munich, Stuttgart,

Leipzig, Essen, Hannover (3x), Berlin (3x), Turin and Milan (2x). Stevie

was flying at the height of the so-called Battle of the Ruhr (Happy Valley) and

the beginning (or prelude) to the Battle of Berlin. He was flying in a period

when Bomber Command losses were at their peak. On 57 squadron in this period,

only 20% of crews survived an operational tour. In the RAF as a whole, 669 aircraft

were shot down over enemy territory, while others crashed on landing as a

result of damage sustained on operations or due to poor weather. Others were

lost in collisions due to the very dangerous conditions of operating at night

without navigation lights in a loose “bomber stream.” Although occasionally one

or two men survived being shot down or crashing, the loss of all seven men on

board was more common.

Stevie

later described the experience as follows:

An operational tour seemed like a series of thirty very testing examinations, requiring skill, intelligence and a grim determination to succeed. A momentary failure to concentrate and react swiftly usually resulted in death…Yet morale was invariably high.”

On another occasion he wrote:

“I was always astonished by the lack of panic among the aircrew who flew on tours. … It was pretty obvious that we couldn’t all survive, and when you looked around the table at a briefing for 18 – 20 crews, you knew darn well the next day that at least two or three wouldn’t be coming back, and perhaps more. As the Captain, you would come out and tr to make a joke or a comment just to lighten the mood and to keep up the morale of your crew.”

For

Stevie, it was this concern for his crew that dominated his thoughts and

determined much of his behaviour. A deeply spiritual and devout man at heart,

he prayed before each flight: “God grant that I may never fail my crew and that

I may ever fulfil the trust they place in me.” His concern for his crew

manifested itself in how conscientiously he did his job, but also in the fact

that to the end of his life his lost comrades remained spiritually with him.

His son remembers that the first time he went to vote, his father (Stevie) told

him: “A lot of my friends gave their lives so that we can do this, and a lot of

them were younger than you.” On another occasion he wrote:

“The world we did our bit to bring about is, for all its

problems, an infinitely better place than the world subjected to Nazi tyranny.

That is Bomber Command’s legacy to the young men and women of today, and it is

a true memorial. They laid down their lives so that you could live yours in

peace and freedom.

But

Stevie showed his respect and concern for his crew in other ways too. When his

rear gunner suffered from PTSD following a particularly harrowing sortie in

which the Lancaster had sustained severe damage, Stevie could not risk flying

with him, but he would not hear of him being posted for “Lack of Moral Fibre” (LMF)

as was then common. Instead, he not only asked the Squadron CO to stand him, in

his own words, he: “I suggested to my CO that [the gunner] might be

commissioned and so avoid being discharged and demoted as LMF. The CO tore me

off a might strip for being so bloody impertinent….” But he was successful. The gunner was

commissioned and later returned to operational flying.

Stevie

ended his tour as a Pilot Officer, having been promoted on 4 July 1943 after

eight operational sorties. He received an immediate DFC, more for his entire

tour than for an individual act of bravery. He was 22 years old and planning to

marry in December. His wife was a WAAF,

a Radio/Telephone operator in Flying Control. She was one of the first women

trained and posted for this trade and the RAF was still adjusting to it. When

diverted to a different field due to a shortage of fuel, Stevie received

instructions to land from a woman the first time in his life. On landing, he

went straight to the Control Tower hoping to make a date with the WAAF — only

to find her surrounded by pilots much more senior than himself. (He was still a

sergeant at the time.) Luck was on his side, however, because just days later

the WAAF R/T operator was soon transferred to his own station. When her voice

again gave him instructions, he recognized it at once, and went straight to the

tower to ask her out! Her name was Maud “Maureen” Miller.

Shortly

after her transfer, Maureen was on duty the night 617 Squadron returned from

the raid against the Ruhr dams. She talked in all the returning aircraft of the

squadron, something that made her a “celebrity” later in life although to the

end, she consistently pointed out she was only doing her job. While she was

friendly with many of the 617 pilots, she fell in love with Stevie. Maureen

remembers him saying: “If I’m still alive at the end of the year, we’ll get

married.” He was, and they did. They stayed together more than seventy years

until Maureen’s death the day before their 74th wedding anniversary

in 2017.

But

they could not know that in December 1943 — a dark period of the war. The

bombing offensive against Berlin was at its peak and taking a terrible toll.

The Allies had not yet landed in Normandy. The end of the war was not in sight.

Stevie, however, was due for at least a break from operations and his next

assignment was as an instructor at an OTU, training pilots on the Wellington. (Note: the photo below was taken just six months after the one above.)

Stevie

recalls that the reception at the OTU was cold and he was at first found the

Wellington a bit of a comedown after flying Lancasters, but he soon came to

appreciate the flying qualities of the Wellington and its suitability for

training pilots on the principles of night operations and preparing pilots to

fly the heavy bombers. Training was dangerous. Roughly 5,000 RAF aircrew died

in training accidents in the course of the war. Many instructors became victims

of student pilots’ mistakes. But Stevie proved a gifted instructor — unlike

many former operational captains. He was so good at instructing that he was not

asked to return for a second tour and did not volunteer himself. He had found

his niche.

Stevie

was sent to the instructors course to become an instructor of instructors. When

the war ended, he was not released but instead promoted to Flight Lieutenant.

He was also sent on additional training courses after which he was assigned as

Wing Adjutant, Station Adjutant and Chief Ground Instructor. Increasingly,

however, his students were not young pilots learning their trade but returned

POWs. These men were often highly experienced pilots, many of them much more

senior than Stevie, some of who had been in POW camps for years. Those who had

been prisoners of the Japanese had often suffered malnutrition, physical abuse

and psychological torture. Some recognized the need for a “refresher course” in

flying; some didn’t. It was not until October 1947 that Stevie was “demobbed”

with the rank of Flight Lieutenant on the condition that he remain in the

RAFVR.

Stevie,

however, had his eye on turning his proven talents as an instructor into a

career in teaching. He attended a teacher training college and, after

qualifying, took up work at secondary schools teaching Science and Maths. It

was a career he was to pursue successfully for nearly forty years with great

success — as the testimonials of many of his former pupils attest.

Stevie’s

RAF career was exemplary in more ways than one. He came from a humble

background, bucked the prevailing class prejudices of the era and took

advantage of the RAF’s comparatively merit-oriented culture to attain first

command and then rank and recognition. He “did his job” as a bomber pilot, yet

it was as an instructor that he really stood out and it was as a teacher that

he impacted the lives of thousands for the better.

(The

information in this bio is drawn from Tomorrow May Never Come: The Remarkable

Life Story of ‘Stevie’ Stevens, Lancaster Pilot and Beloved School Teacher

by Jonny Cracknell and Adrian Stevens. This biography is available for purchase

at: https://jonnycracknell.com/tomorrow-may-never-come/ )

My novels about the RAF in WWII are intended as tributes to the men in the air and on the ground that made a victory in Europe against fascism possible.

Lack of Moral Fibre, A Stranger in the Mirror and A Rose in November can be purchased individually in ebook format, or in a collection under the title Grounded Eagles in ebook or paperback. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

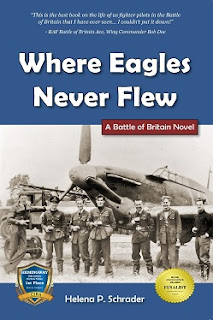

Where Eagles Never Flew was the the winner of a Hemmingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew

No comments:

Post a Comment