In the course of WWII, 28 men won Britain's highest award for bravery, the Victory Cross, while flying with the RAF. All demonstrated remarkable devotion to duty and physical courage, and sixteen of them gave their lives so that we will never know what they might have done in peace. Of the survivors, however, one man stands out even in this distinguished company: Leonard Cheshire.

Cheshire

stands out on three counts. First, he combined personal courage with devotion

to the welfare and well-being of the men under his command. Second, he was

unconventional and innovative in his thinking and approach to problems,

significantly impacting Bomber Command tactics at a critical time. Third, he devoted

his life after the war to helping people, first by learning nursing and

personally caring for others, later by establishing foundations dedicated

to aiding those with disabilities -- which still exist today. In short he combined courage with compassion

to an unusual degree. A short biography follows.

Geoffrey Leonard Cheshire was born into the British ruling elite, the son of a barrister and legal scholar. He went to the best schools and attended Oxford University where he studied law, graduating in 1939 — albeit not with first class honors as was expected by his family. Yet more important than his academic activities in this period is that he won a bet that he could walk all the way to Paris starting only with a few pennies in his pocket. Equally important, he visited Germany in 1936 staying with Ludwig von Reuter, a highly decorated German naval officer responsible for scuttling the German fleet at Scapa Flow in June 1919. During his stay in Germany, Cheshire attended one of Hitler’s rallies and demonstratively refused to give the Nazi salute. Last but not least, while studying at Oxford, Cheshire joined the Oxford University Air Squadron and learned to fly. As a result, he already held a commission as a pilot officer at the start of WWII.

At the outbreak of the war, Cheshire was summoned for active duty and assigned (to his disappointment) to Bomber Command. After operational training, he was promoted to Flying Officer and posted to 102 (Whitley) Squadron in April 1940. Cheshire related in his memoirs that at the time he was afraid of not measuring up. He credits his later success to the intense mentoring he received from Hugh “Loffty” Long, with whom he initially flew as Second Pilot. In addition to giving him opportunities to fly while on operations, Long demanded very high standards and drilled Cheshire on procedures blindfolded while on the ground. Long also made Cheshire become familiar with the duties of the gunner, navigator and wireless operator, making him sit in their places and see the world from their perspective. Cheshire flew ten operational flights as “second dickey” to Long before being given command of his own aircraft in June 1940.

Cheshire earned his first decoration on the night of Nov. 12/13 1940. On finding the target (the synthetic oil plant at Wesseling) obscured by fog, Cheshire decided on his own initiative to drop his bombs on the railway yards of Cologne. Unfortunately, his aircraft was bracketed by flak. Cheshire was temporarily blinded and a huge hole was torn in the aircraft, igniting one of its flares. On fire, the aircraft went into a steep dive. While Cheshire regained control of the aircraft, his crew fought the fire. When the fire was extinguished, a hole stretched along the port side from the wing almost to the after hatch. However, both engines were still working and the aircraft seemed to be flying well enough, so Cheshire decided to make a renewed approach on the target and drop his bombs. His tour with 102 Squadron ended in January 1941 and he immediately volunteered for a second tour.

Cheshire’s next tour was with 35 Squadron, which had just been outfitted with the four-engine Halifax bomber. He flew on seven operations against Berlin in this period and was promoted to Flight Lieutenant in April 1941. When the squadron was stood down in May while Bomber Command attempted to redress design flaws in the Halifax, Cheshire took the opportunity to volunteer for a temporary posting to the Atlantic Ferry Organization. This gave him an opportunity to see a little of America. His return, however, was delayed by bureaucratic glitches, so when he finally flew a Hudson back to England, it was to discover on arrival that all but one of his crew had been killed on an operation during his absence. Although he was badly shaken by these losses, he formed a new crew and completed his tour with 35 Squadron in early 1942 with a total of 50 operational sorties.

Cheshire next served as a flying instructor at an operational training unit, but continued to fly on operations when calls were made for a “maximum effort” — something that happened frequently in this period shortly after AVM Arthur Harris took over Bomber Command. During a sortie to Berlin in which his brother was also flying, his brother’s aircraft went missing. Meanwhile, Cheshire had been promoted to Squadron Leader and flight commander.

Whether by chance or intent, shortly afterward, the RAF saw fit to appoint Cheshire CO of his brother’s former squadron, No 76. He took over at a time when the squadron had been badly decimated and morale was low. Cheshire tackled the moral problem by employing an extremely personal leadership style. He made a point of knowing the names of everyone on his squadron — officers and other ranks, air and ground crew both. He took time to talk to them, to become familiar with their personal lives. This approach earned Cheshire praise, particularly from the “other ranks” who served under him. Despite the RAF’s vaunted meritocracy, many men without wings felt keenly that the RAF was still a pilot’s club. Cheshire, they claim, was one of the few senior officers (he was by then a Wing Commander) who showed as much interest and respect for a gunner or a rigger as he did for a pilot.

Furthermore, although ordered to fly no more than once a month unless “absolutely necessary,” Cheshire ignored those orders and flew every difficult operation. When flying, he either flew Second Pilot to a sprog pilot to help build the confidence of the newcomers, or he flew first pilot with an experienced crew while leading a particularly risky operation. Just as he disobeyed orders about flying less, he also ignored orders he thought were stupid — such as flying at 2,000 feet over concentrations of flak.

Yet Cheshire distinguished himself from other conscientious commanders by going beyond good leadership and setting a good example. Cheshire also tried to solve the increasingly worrying design problems with the Halifax. Halifax losses were excessive. Few could return on three engines (unlike, for example, the Lancaster that could fly on two quite well and occasionally made it home on only one engine). Equally dangerous was that the Halifax appeared unstable in a “corkscrew,” the standard evasive tactic for bombers attacked by fighters. Cheshire personally joined the test pilot looking into the problems in an effort to understand the situation better. After this experience, he ordered modifications to his squadron’s Halifaxes to make them lighter and so able to fly higher and faster.

At the end of his third tour, Cheshire was promoted to Group Captain at the age of 25; he was the youngest Group Captain in the RAF at the time. Effective 1 April 1943, he was appointed Station Commander at Marston-in-Marsh. It may have seemed like an April fool’s joke to him, as he immediately encountered difficulty with red tape and a bureaucratic mentality among the permanent staff that was alien and anathema to him. He had hardly started his new job before he started trying to get out of it again — and back to operational flying. Maybe out of frustration, he wrote and published his first book, Bomber Pilot, during this phase of his life.

In September 1943, the C-in-C of 5 Group Ralph Cochran asked Cheshire if he would be willing to assume command of No 617 Squadron, famous as the “Dambusters.” Although such a posting would require him to surrender his promotion and revert to the rank of Wing Commander, Cheshire jumped at the opportunity. Cochran required him to do a conversion course onto the Lancaster before starting, which Cheshire did with marked humility. Other trainees remember him meticulously asking questions especially of men flying in other trades (e.g. Flight Engineer, Bomb Aimer etc.)

Cheshire had been recruited by Cochrane to help solve a pressing problem. With their backs increasingly to the wall, the Germans had unleashed their creativity to develop four devilishly advanced and potentially game-changing weapons. Two of these were early forms of missiles, or “flying bombs,” the familiar V1s and V2. The third was huge, long-range guns being installed in the Pas-de-Calais, and the fourth was the mostly battery-powered XXI-type submarines with underwater speeds faster than most merchantmen. All of these super-weapons were being constructed and installed in “hardened” sites protected by reinforced concrete meters thick. The RAF had to find a means to penetrate those concrete walls and destroy the weapons underneath. The engineering genius Barnes-Wallis, famous for developing the bouncing bombs that had destroyed the Ruhr Dams, had already come up with a new bomb. This so-called “Earthquake” bomb if dropped from 18,000 feet or more could reach supersonic speeds and penetrate meters thick concrete. The problem was that the bomb was only effective if delivered very precisely — within 12 meters of the target.

Cheshire’s challenge was to find a way to mark a target so precisely that bombs could be delivered within 12 meters from 18,000 feet or more. The marking techniques then in use were woefully inaccurate as an attempt by 617 to take out a V-1 site in January 1944 proved. 617 Squadron led by Cheshire succeeded in dropping all their bombs within less than 100 yards of the target, but the Pathfinder that had marked the target had dropped the flare 350 yards off the target and all the subsequent accuracy had been in vain.

Using this example, Cheshire convinced AVM Harris to allow him to develop his own marking techniques. Eventually, after intensive experimentation on the bombing range, Cheshire and the pilots working with him developed a technique involving a combination of illuminating flares that enabled a low-flying aircraft to deliver a marking flare very precisely by dive-bombing down to 100 feet. Cheshire proved the concept with — of all aircraft! — a Lancaster.

Cheshire and 617 Squadron demonstrated the effectiveness of the technique in a raid on the aero-engine factory in Limoges, France. Cheshire first flew over the factory at 20 feet to warn the French workers. They got the hint and ran out. Then he dropped the marker flare on the roof of the factory and called in the remaining aircraft of 617 one at a time. The factory was obliterated without a single casualty on the ground.

Further experience showed that the marking could be accomplished better by a lighter and more maneuverable aircraft such as the Mosquito, and Cheshire was loaned several that he then employed highly effectively on a variety of raids including Munich, V1 and V2 sites, and E-boat pens. When the RAF later took Cheshire’s borrowed Mosquitos away, he obtained a Mustang from the USAAF — and flew it for the first time on June 25 to lead a daylight raid against a launch site for V1 flying bombs. His ground crew literally finished assembling the Mustang after the Lancasters of 617 had already taken off. Cheshire climbed into the Mustang and took off without a test flight to overtake his bombers and place the marker flares. He arrived on schedule and succeeded in marking the target accurately. The V1 site was destroyed.

On 6 July 1944, Cheshire led 617 in an attack on the V3 site and utterly destroyed it, removing this “wonder weapon” from Hitler’s arsenal altogether. The following night, July 7/8 Cheshire flew his 100th operational sortie. In his Mustang he marked a V1 and V2 storage site hidden in the caves at St. Leu d’Esserent, and 617 Squadron using Barnes-Wallis “Tallboy” bombs caused the caves to collapse. Immediately following, he was taken off operations on Cochrane’s orders and command of 617 Squadron was turned over to another officer.

Cheshire was awarded the Victoria Cross for his four years of outstanding service and four operational tours. Characteristically, as his investiture at Buckingham Palace, which did not take place until Oct. 1945, Cheshire told King George VI that the warrant officer receiving the VC at the same time, Norman Jackson, should receive his VC first. Jackson, a Flight Engineer, had crawled out of the cockpit of a damaged Lancaster with a fire extinguisher in order to put out a fire to one of their engines that threatened to reach the fuel tanks. He was badly burned in the attempt and blown off the wing, but survived in German captivity.

Cheshire served as one of the official British observers at the bombing of Nagasaki, and six months later in January 1946 resigned from the RAF due to disability. Immediately, he became involved in an unstructured charitable venture, namely turning his home into a “colony” for veterans and war widows, in which the inhabitants lived together in a community to help transition back to civilian life. Demand for space was great, so he bought a mansion from his aunt, but the communal experiment did not work out and closed in 1947. One of the participants, however, had developed cancer and asked Cheshire for land where he could park a caravan until he “recovered.” Cheshire instead invited him into his home and learned nursing skills to look after him as he was, in fact, dying.

Soon there were others. Some came because they were terminally ill. Some came to help. Finances were improvised. Cheshire realized the situation was not sustainable and so sought to institutionalize his work by registering a charitable organization, the Cheshire Foundation Homes for the Sick. The concept was that volunteers in a community would come together, identify suitable accommodation and raise funds. Today known as the Leonard Cheshire Disability charity, the registered aims are: "to provide effective and efficient community-based services to disabled people that respond to their preferences" and to "campaign in partnership with disabled people, allies and supporters for a society that provides equality to disabled people."

Cheshire devoted the rest of his life to this cause. This included founding a second foundation with his wife Sue Ryder, the Ryder-Cheshire Foundation dedicated to the rehabilitation of the disabled and the treatment of tuberculosis. In 1953 he also founded the Raphael Pilgrimage to assist pilgrims to travel to Lourdes. In 1990 he founded the Memorial Fund for Disaster Relief. He died 31 July 1992.

My novels about the RAF in WWII are intended as tributes to the men in the air and on the ground that made a victory in Europe against fascism possible.

Lack of Moral Fibre, A Stranger in the Mirror and A Rose in November can be purchased individually in ebook format, or in a collection under the title Grounded Eagles in ebook or paperback. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

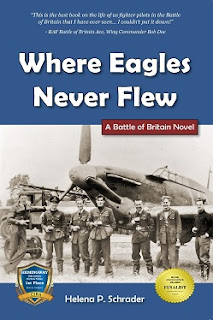

Where Eagles Never Flew was the the winner of a Hemmingway Award for 20th Century Wartime Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew