In the Battle of Britain, Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding faced a Luftwaffe led by Reichsmarshall Hermann Goering. As overall C-in-C of the Luftwaffe, Goering was not technically Dowding's military counterpart. Yet Goering's interference in the Battle and his high-profile leadership style make if fair to say that Goering and Dowding faced off against one another.

Two more different men are hard to imagine. While Dowding was retiring and unassuming almost to a fault, Goering was bombastic and loved the limelight. Yet it would be wrong to dismiss Goering as a clown or a fat buffoon. He was far more dangerous, sinister and complex than such a portrayal suggests.

Goering was born into the ruling elite and raised in a castle belonging to his mother's Jewish lover. He was commissioned in the Army at aged 19, two years before the start of WWI. During the war he transferred to the fledgling air force, and as a fighter pilot had twenty-two credited victories, for which he was awarded the "Pour le Merite" or "Blue Max" -- the highest German medal at that time. He took over command of Manfred von Richthofen's famous fighter wing after Richthofen's death in July 1918.

Goering could not come to terms with Germany's defeat and went into voluntary exile in Sweden, where his good looks and daring flying won him admirers and social success -- including captivating the wealthy Swedish baroness, Carin von Rosen. Their affair scandalized the Swedes, however, and they fled to Bavaria where they married in 1923 after Carin divorced her first husband. Meanwhile, Goering had met and become mesmerized by Hitler, whom he met in 1922. Despite their differences of class and personality, the bond between the two men was to hold almost to the last day of Hitler's life. Despite his later failings, Goering always retained a place of privilege in Hitler's inner circle that neither Goebbels or Himmler could displace.

Goering earned that place with his early dedication, sacrifices and effectiveness. Goering took over the Sturm Abteilung (SA) -- Hitler's thugs -- and turned them into a (comparatively) disciplined troop capable of much more effective disruption, brutality and intimidation. Despite his best efforts, however, the SA did not prove a match for the Bavarian police and Goering was wounded in the groin during the abortive "Beer Hall Putch" of 1923.

While convalescing, he was forced to surrender command of the SA to Ernst Roehm. His treatment, furthermore, entailed morphine and he soon became addicted. The addiction caused mood swings, weight gain, and led him to the brink of ruin. He was twice institutionalized for addiction in Sweden, and meanwhile he and his wife bankrupted themselves with donations to the Nazi Party.

In May 1928, however, he was one of only 12 men elected to the Reichstag on the Nazi Party slate. This provided not only a salary, but respectability and a platform from which to work. He proved to be a gifted fund-raiser and recruiter, equally at ease in upper-class cocktail parties or out haranguing workers and farmers. By September 1930, the Nazi party had increased its seats in the Reichstag to 107. Two years later it was 230 -- and Goering was the President of the Reichstag (equivalent to the Speaker of the House in the U.S.).

Goering used his position to systematically undermine democracy, something he managed in part because of his good relationship with the increasingly senile Paul von Hindenburg, the official Head of State or Reichspraesident. When Hitler, as the leader of the largest faction in the Reichstag, was appointed Reichschancellor, Goering was appointed Minister of the Interior in Prussia, a position he used to establish the Gestapo and the first concentration camps. He may also have played a role in orchestrating the fire in the Reichstag that became the pretext for Hitler demanding -- and receiving -- dictatorial powers.

In the first years of the Nazi regime, Goering was Hitler's unquestioned "right-hand-man" and his bulwark. In addition to using the Gestapo and Concentration Camps to purge the country of opposition leaders, independent journalists and other democratic elements, he used threats and bribery to bludgeon and seduce support from Germany's industrial elite. In 1934 he took his revenge on Roehm for replacing him as head of the SA by masterminding the slaughter of the SA leadership during the completely fabricated "Roehm Putch" -- an orgy of murder against some of the Nazi party's most loyal (and brutal) supporters. The purge has gone down in history as the "Night of the Long Knives" although it lasted three days. (Below Ernst Roehm.)

Although Goering surrendered control of the security apparatus to Himmler in the aftermath of this purge, in 1936 he was entrusted with ramping up Germany's synthetic oil and rubber production. He was so successful that Hilter appointed him Minister of Economics in 1937. He used this position not only to build autobahns, ramp up steel production, improve harvests and reduce unemployment, but to build up armaments, stockpile munitions and other war materiel -- and to enrich himself.

His appetite for luxury and display along with fine art, fine wine and good food was insatiable. He designed ever more flamboyant uniforms for himself, built a huge hunting lodge, maintained dozens of personal cars, had a personal armed train with a hospital car (among other things). He wore rings on every finger, and when he remarried in 1935 (his beloved wife Carin had died of a heart attack in 1931, aged only 38), he had a wedding parade with 30,000 soldiers.

All the while he was head of Germany's civil aviation and the secret Luftwaffe, which came out of hiding in 1935. Goering attracted highly competent men to the new and prestigious organization, men like Walter Wever, Hans Jeshonnek, Ernst Udet and Erhard Milch. The Luftwaffe also enjoyed priority in recruitment and huge budgets. It grew rapidly and benefitted from a sophisticated German aeronautics industry. The Spanish Civil War provided an excellent testing ground for men and machines before the outbreak of WWII. Among other things it demonstrated that the Stuka dive bomber (shown below) could be a highly successful ground support and terror weapon.

The Luftwaffe, whose machines and tactics had largely been devised for close combat support roles, was instrumental in Germany's victories over Poland and France. These successes combined with Goering inflated sense of self-worth led him to promise Hitler that the Luftwaffe would destroy the BEF at Dunkirk and then that it would force Britain to surrender.

But Goering had never been more than a captain (Squadron Leader). He had never gone to staff college, much less served in a staff position. He had no first hand experience with modern aircraft, and no understanding of modern fighter tactics. His interference in the direction of the Battle of Britain was counterproductive -- including backing Kesselring's demands to attack London. Goering probably did so for political reasons -- to bolster his own prestige (which was tarnished by RAF attacks on Berlin and other German cities, although these raids were no more than pinpricks at the time). He was also motivated by the need to regain favor with Hitler, who wanted revenge for the attacks on Germany. Whatever his reasons, the targeting of London took the pressure off Fighter Command's airfields and helped ensure RAF withstood the attacks long enough to force a postponement of the invasion.

The Luftwaffe never regained it's mastery -- despite such brilliant technical advances as the FW190 (that for nearly a year out-classed all allied fighters) or even the ME262, which was even more superior. Technical genius could not make good the steady attrition in machines, men and morale that set in on the Western front. Meanwhile success in the East was also ephemeral. Despite much higher kill-to-loss ratios, the sheer size of the task and the weather eventually took its toll. Goering, meanwhile, remained out of touch with reality and vastly overestimated his own and the Luftwaffe's capabilities. Among other errors, he promised to supply the Sixth Army, trapped at Stalingrad, entirely by air. It couldn't be done. Goering -- and the Luftwaffe -- "failed" again.

Goering played only a nominal role in the waning years of the Third Reich. He was tried at Nuremburg and condemned to death. His sentence was earned many times over. He had been ruthless, undemocratic, and corrupt ever since the Nazis came to power. He was personally responsible for a variety of crimes from the establishment of the Gestapo and the early concentration camps to the murder of hundreds in the purge of 1934.

Yet while he shamelessly stole assets from Jews, he also held his hand over those he personally liked (or thought useful) with the famous phrase: "Wer Jude ist bestimme ich." (I decide who is a Jew.) Likewise, a glimmer of honor emerges from his refusal to expel air force personnel implicated in the July 20th Plot from the Luftwaffe. Unlike the army that unceremoniously threw their former comrades to the Gestapo and so knowingly allowed them to be tortured and executed, Goering had all Luftwaffe officers tried before military tribunals. They were not tortured and some were allowed to "redeem themselves" on the front.

Goering took his own life rather than facing being hanged like a common criminal on Oct. 15, 1946.

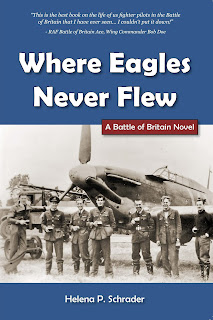

Goering has only a cameo role in "Where Eagles Never Flew."

Yeah, Adolf knew how to find them alright. Or "attract" them. whichever you prefer.

ReplyDelete