My novels usually feature strong female leading characters. Yet because I write historical fiction, they sometimes pose unique challenges. Human nature may have changed little over the centuries, but acceptable female behaviour varies greatly across both geography and time. In keeping with my objective of creating novels which authentically convey the atmosphere and ethos of the period in which they are set, my female characters cannot be modern women in period costume; they have to share the values and respect the restraints of the age in which they "live." This was true of the female lead in "Moral Fibre" no less than novels set in Ancient Sparta or the era of the crusades.

The female protagonist of Moral Fibre is Georgina Reddings. Unlike the hero, Kit, she was shy about communicating with me directly. I knew her first and foremost through Kit's eyes and only gradually pieced together more about her. Slowly, step-by-step, she emerged out of the shadows as her natural modesty and reticence melted and she took shape as a full-blown character in her own right.

Georgina was the daughter of a rural vicar in West Yorkshire. She enjoyed a carefree and comfortable childhood, attending a girls boarding school run by the Church of England. The Victorian vicarage with its large barn made it easy for her to indulge her passion for horses, riding and hunting, and she was a bit "horse crazy" as a young teenager, but the war soon sobered her. In 1942 she started studies at the Lincoln Diocesan Teachers Training College, with the goal of becoming a secondary school teacher. At at dance at the Lincoln Assembly Rooms, she met and instantly fell in love with the shy, serious and gentle Don Selkirk, a Lancaster skipper from a nearby RAF station.

Scion of a wealthy, Scottish gentry family, Don bedazzled Georgina, without even trying. They became engaged within four months of meeting, to the delight of both sets of parents. Don's parents found Georgina sweet and innocent, modest and malleable. Her parents saw in Don the perfect gentleman with a law degree and good prospects after the war. Meanwhile, he was protective and considerate in every way. He cocooned Georgina in a sense of safety. He encouraged her to continue her studies, yet indulged her hopes, visions and plans for a future together. He assured her he had always been lucky and that nothing would happen to him.

And then he was dead. A 20 mm cannon of a German night fighter having hit his heart and killed him instantly. Georgina's entire world fell apart. She hadn't just lost the only man she'd ever loved, she'd lost her dreams and hopes for the future as well. All at the age of 19.

Georgina's grief was as great as her heart and her capacity for love. It shocked the under-cooled society around her, which expected a "stiff upper lip," "restraint," "self-control." After all, Don was only one of 55,000 airmen who were to die, and civilians were being killed every day too. There was no room in wartime Britain for too much grief. Instead, the emphasis was on all those established British virtues that had won and Empire and were more vital than ever in this, their "finest hour." Her friends and colleagues at the college were alienated. Her parents feared for he sanity. Her doctor thought she needed psychiatric treatment.

The only one in the whole world with whom Georgina could share her grief without reproach or inhibition was with Don's best best, his flight engineer Kit Moran. But Moran was in trouble, having refused to fly after Don's death. He was posted off his squadron and sent to a RAF diagnosis center. His future was under a cloud, and he told Georgina that he believed it would have been better for all if he had died in Don's place.

Georgina denied it, and with that recognition that Kit too was a valuable life that might also have been lost, she started groping and stumbling along a path out of her underworld of grief. She clung to Kit as a lifeline connecting her both to Don through his memories and shared experiences and to life. Although Kit was soon posted to a training station in South Africa, they corresponded. Georgina wrote two to three times each week, pouring out her feelings and by writing down her thoughts coming to terms with her loss bit by bit.

Then, in August 1942, Kit returned to the UK to start operational training. Since his family was in Nigeria, naturally Georgina invited him to spend his disembarkation leave at her home with her parents. And there they met again. Suddenly, their relationship wasn't all about Don and the past. Kit was in love with her. But Georgina was terrified of committing her heart again when Kit was facing a tour of operations in a war that was as intense as ever.

Next week I will introduce the two antagonists: Red Forrester and Fiona Barker.

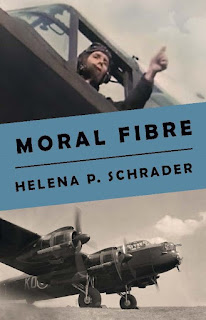

Riding the icy, moonlit sky— They took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were

less than fifty percent. Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one Lancaster

skipper, his crew,and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to

them all.

Order Now!

Flying

Officer Kit Moran has earned his pilot’s wings, but the greatest challenges

still lie ahead: crewing up and returning to operations. Things aren’t made

easier by the fact that while still a flight engineer, he was posted LMF

(Lacking in Moral Fibre) for refusing to fly after a raid on Berlin that killed

his best friend and skipper. Nor does it help that he is in love with his dead

friend’s fiancé, who is not yet ready to become romantically involved again.

.jpg)