Today I conclude my series on "Forgotten Heroes

of the Air War 1939-1945" with a guest entry from Susan Martin of

Cumberland Maine. Susan writes about her father, Lieutenant Douglas Starrett,

who commanded a B-17 of the US Eighth Air Force in 1944-1945. Like

"Stevie's" story, his tale is less about exceptional acts of courage and

more about the spirit of dedication and commitment that so often characterized

the men who flew for the Allies in WWII.

"What does it matter how you feel about that? It

has to be done."

"Self-discipline!"

When I was growing up, I never thought to ask why or how my father

came to use such strong statements with me. Or why, whenever something went

wrong, or in an emergency, my Dad got very quiet, very controlled and took care

of everything. Only later did I start to think it had something to do with the

fact that he had been the captain of a bomber plane in WWII. When he was alive,

I never asked him about his experiences — and he never told me anything either.

Yet I vividly remember one time as a teenager coming upon him

watching a black and white movie on TV. His jaw was tensing, his fists

were clenching and he didn't even know I was looking at him. Quietly,

I left the room, found my Mom and asked her what was wrong with

him. Her answer: "Oh he's just watching 12 O'Clock High

again!" Of course, I watched it myself as soon as I could. I

was shocked at the combat footage (some actually filmed during air battles) and

came away in a bit of awe...wondering how anyone could function, let alone come

back alive. My father was one who did, and this is his story.

My father was born in April 1920 in Framingham, Massachusetts, the oldest son

of Arthur Starrett, the president of L.S. Starrett Tool

Company. He was followed by a brother and

sister. After completing high school in Athol, Massachusetts, Dad went to Worcester

Academy in 1937 for one year and then to Dartmouth College. He had not yet

completed his junior year when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and Hitler

declared war on the United States. Returning home after completing his junior

year exams at Dartmouth College, he informed his father that, like many other

young men at that time, he did not intend to return to college but was going to

join the Air Force instead. It ended up being an all-night-long fight with his

father Arthur, but my Dad won the fight. He joined the USAAF.

He also got married to my mother, Janet Nichols. He was 21

& she was 22. She had just graduated Skidmore College. After

they got married, he took my Mom with him to Florida while he went

through pilot training. Married airmen at that time could bring

their wives and they lived off-base in apartments.

My father won his wings at Freeman Field, Indiana in March

1944. Further, training followed, until he was fully qualified on the four-engine

B-17 bomber. On completing training, he was assigned to the USAAF 8th

Air Force. The legendary “Mighty Eighth” was based in England and leading the

U.S. strategic bombing efforts against Nazi Germany.

My mother could not accompany

my father overseas. She chose to live with her parents, while my father deployed

to England. It must have been a scary time for both of them. He was facing the

enemy day-after-day and with it the constant threat of death. All my mother

could do was wait for his letters — while reading everyday how many B-17s had

been shot down. She knew the risks all too well — and so did he. According to

my mother, they had refrained from starting a family before the war because my

Dad didn't want to leave her a widow with a child. I would not be born

until 1946.

My father joined the 486 Bombardment Group, Eighth Air Force,

Third Air Division, stationed at Skipton Airbase. He was lucky to arrive so

late in the war. In 1943, airmen flying with the USAAF from England had only a

one in four chance of completing their tour. Average life expectancy was 15 missions,

and a tour was 25. By the time my father completed training, however, the

long-range fighters, the P-47 Thunderbolt and P-51 Mustang, had joined the fight, and

the Luftwaffe had largely been destroyed. Chances of survival had improved so

much that the USAAF increased the length of a tour from 25 missions to 35. And

while the threat from the Luftwaffe had decreased, the German anti-aircraft

batteries, the infamous “flak,” was as bad or worse than ever. As captain, my Dad was the pilot and if it were damaged, it was

his job to stay in his seat and try to keep the plane level and on an even keel

so his crew could bail out. He would be last to man to parachute out —

assuming the plane didn’t spin out of control as soon as he stopped flying it,

that is!

On March 30, just a few days after Dad flew his last mission, his former B-17 went down over Hamburg. According to squadron records, one of

the aircraft wings broke off and it went into a steep dive. Only two crewmen

survived to become POWs. Yikes !!! It guess it was bad karma for the new

crew to change the name of the plane my Dad piloted on 35 missions and which

had always brought him and his crew home from "Lil Butch" to “Rodney the Rocks.”

Not that my father never had problems. I remember my Dad saying that the B-17's, the Flying Fortress,

could take a lot of hits and still remain flying. I later learned that he had to

land once in France because he was so badly shot up that he knew he couldn't

make it back over the English Channel. An account of this appeared in his local hometown news paper on March 19, 1945. The headline read: "Athol Pilot

Saves Fort" "Lt. Starrett Lands Damaged Bomber in Nick of

Time"

To paraphrase, his gasoline was just about gone, the

navigational equipment and radio destroyed, but flying in

bad weather through a heavy cloud cover, he managed to land his

plane and crew safely on a field not too far from Paris. He had flown through

heavy flak over railroad yards in Munich Germany, dropping his bombs but being

shot up pretty badly. "We hit that runway at the right minute"

said my Dad. "The needles on those gas gages were kicking around like they

wanted to jump out and do a tap dance on the instrument

panel"

He, his crew and plane stayed overnight on that field for

emergency repairs and service so they could make it back across the Channel the

next day. Before they flew back to Britain, a local priest brought a

group of over 60 children from a nearby village. They had often seen these

large armadas of B-17s flying over their village but had never seen one

close-up. Dad's crew took the children out to their plane where they

excitedly swarmed all over it, asking questions in French and broken

English. They were particularly excited to learn that each bomb painted

on the big bomber's nose indicated one successful attack on a war target in

Germany. When the bomber finally took off down the runway, the kids

cheered, waved and gave the V-Sign.

After the war, my Dad did not go back to Dartmouth but went

right into the 4-year apprentice toolmaker's program at L.S. Starrett

Co. Back then, even if you were aiming to advance up the ladder, a

college degree wasn't as important as it is now — at least that was my Mom’s

explanation for why my Dad never finished college. I think that his war

experiences also matured him, and he felt that he wasn't a college boy

anymore. He wanted to get on with his career, married life and start a

family. I was born in 1946, a year after he left the Air Force,

followed by my sister Sarah and brother Douglas.

Dad's Father Arthur was not going to just put his son into the

executive office. Instead, my Dad had to learn about the tools the factory sold

at first hand. He had to work in all the departments as he worked his way up

the ladder. Eventually he became President and the CEO of the

company. He established overseas branches in Scotland & Brazil and was

still working at the time of his death at 81 years old in Nov. 2001.

Once as a teenager, I was on a commercial flight with Dad, and

it really got rough and bumpy. I was scared and told my Dad. He said,

"What are you afraid of? No one is shooting at us." Then

I asked him, "Dad you kissed your wedding ring when we took off...how

come?" He replied, “I kissed the ring every time we took off for a

bombing run over Germany, and I always came back!"

Susan Starrett Martin, age 75, Cumberland Maine

USA

My novels

about the RAF in WWII are intended as tributes to the men in the air and

on the ground of whatever nationality that made a victory in Europe against fascism possible. Find out more at:https://www.helenapschrader.com/aviation.html

Lack of Moral Fibre, A Stranger in the Mirror and A Rose in November can be purchased individually in ebook format, or in a collection under the title Grounded Eagles in ebook or paperback. Find out more at: https://crossseaspress.com/grounded-eagles

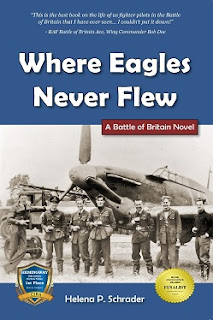

Where Eagles Never Flew

was the the winner of a Hemmingway Award for 20th Century Wartime

Fiction and a Maincrest Media Award for Military Fiction. Find out more

at: https://crossseaspress.com/where-eagles-never-flew