Dominated by the unified and omnipresent Catholic church, every man and woman in Medieval Europe knew about deadly (also cardinal) sins. These sins, according to Catholic theology, are behavior or feelings that are dangerous because they often lead humans to commit a mortal sin, the latter being an act that, unless repented and absolved, can lead to "spiritual death." A look at the seven sins recognized in the middle ages as "deadly" tells us a great deal about the emotions and behavior that medieval man considered morally reprehensible.

The seven deadly sins were: envy, gluttony, greed, lust, pride, sloth and wrath. Obviously some of these sins still strike us as anti-social behavior. Wrath, for

example, is something no one would recommend and most people would agree brings

harm – usually not only to the intended target. Likewise, no matter how tolerant modern

society may be of sexual freedom for consenting adults, lust remains a

dangerous emotional force behind many modern crimes from child abuse and rape

to trafficking in persons. Finally, envy is still seen as undesirable.

Yet greed has more recently been praised as “good” – some people in modern society equating it with ambition and the driving force behind capitalism and free private enterprise. Even more striking, “pride” is something we hold up as a virtue, not a sin. We are proud of our country, proud of our armed forces, proud to be who we are – or at least we strive to be. And who nowadays would put “gluttony” or “sloth” right up there beside lust, wrath and envy?

Yet greed has more recently been praised as “good” – some people in modern society equating it with ambition and the driving force behind capitalism and free private enterprise. Even more striking, “pride” is something we hold up as a virtue, not a sin. We are proud of our country, proud of our armed forces, proud to be who we are – or at least we strive to be. And who nowadays would put “gluttony” or “sloth” right up there beside lust, wrath and envy?

Yet it is precisely these deadly sins that tell us the most about what the types of behavior Medieval Society particularly feared.

In

a society where hunger was never far from the poor and famines occurred

regularly enough to scar the psyche of contemporaries, excessive consumption of

food was not about getting fat it was about denying others. Because there were always poor who did not

have enough to eat just around the corner, someone who indulged in gluttony

rather than sharing excess food was violating the most fundamental of

Christian principles. Nothing could be more essential to the concept of

Christian charity than giving food to the hungry. Therefore person who not only

kept what he/she needed for himself but engaged in excess eating was especially

sinful. Greed was seen in the same light -- as taking more than one's "fair share" of finite resources.

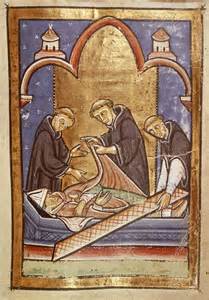

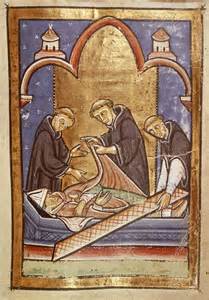

Sloth

is the other side of the same coin. In a

society without machines, automation or robots, the production of all food,

shelter and clothing depended on manual labor. Labor was the basis of survival,

and survival was often endangered. Medieval society could not afford for any

member to be idle. Even the rich were not idle. Medieval queens, countesses and

ladies no less than their maids spun, wove and did other needlework – when they

weren’t running their estates and kingdoms. The great magnates of the realm

were the equivalent of modern corporate executives, managing vast estates and

ensuring both production and distribution of food-stuffs. The gentry provided

not just farm management but the services now provided by police, lawyers and

court officials. In medieval society every man and woman had their place – and

their job. Whether the job was to work the land or to pray for the dead, it was

a job that the individual was expected to fulfill diligently and energetically.

Sloth was a dangerous threat to a well-functioning society.

As for pride, the issue here was the fundamental medieval belief in God's Will. The prevalent belief of the Middle Ages was that each man was born into a specific place in society by the Will of God. It followed that just as no man had the right to be ashamed of his station in life, since that amounted to doubting God's wisdom in putting him there, he should not be proud of his wealth or status either because God had put him there and he should be thankful not proud. In other words, the greater one's status, wealth and success, the more humble one ought to be for God's Grace. Thus while other sins violated the Christian ideal of relations between men, pride violated the proper relationship between man and God. As such, it was the most egregious of all the deadly sins, and often leads the list in medieval texts.

For readers tired of clichés and cartoons, award-winning novelist Helena P. Schrader offers nuanced insight to historical events and characters based on sound research and an understanding of human nature. Her complex and engaging characters bring history back to life as a means to better understand ourselves.