Cold Peace was designed to tell the story of the Berlin Airlift from a variety of perspectives. In consequence, no one character is dominant. Yet to the extent that there is a lead character, it is Wing Commander Robert "Robin" Priestman, the newly assigned RAF Station Commander at the only airfield in the British Sector of Berlin, Gatow. By the end of the Airlift, Gatow was the busiest airport in the world, with more average daily traffic than New York's La Guardia. But in November 1947 when Priestman receives his new assignment, it certainly didn't look that way and there was no reason to think the situation is about to change any time soon.

Excerpt 1:

Of all the RAF airfields in the British Empire, why did he have to land in Berlin? The word conjured up Hitler’s voice and the unique way he harangued and threatened. It brought back the sound of unsynchronised engines groaning across the sky, the jangling of the telephone, the squawking of the tannoy, the sirens and the crump of bombs. He had only to look around to see the scars left by those bombers. London had “taken it,” but at a high price. Gaps like broken teeth marred every row of buildings as far as he could see.

More insidious, however, was the association of “Berlin” with the Gestapo — the ominous threat over seventeen months in captivity during which the Luftwaffe guards hinted that they would have been more comradely, more compassionate, more generous, if only “Berlin” weren’t looking over their shoulders, if only “Berlin” didn’t threaten to kill all the prisoners, if only “Berlin” with its torture chambers did not await the rebellious and the runaway….

Yet such feelings were irrational, Priestman reminded himself. That Berlin had been obliterated, crushed, eradicated. Hitler was dead, his minions were arrested, tried, and hanged. The Gestapo did not exist anymore. The victorious Allies controlled Berlin, and their joint occupation forces patrolled the streets and the skies, a constant reminder of Germany’s utter defeat and unconditional surrender. Why on earth should he dread an assignment to Berlin so viscerally?

Was it just the fact that he was being grounded again? He’d been counting on a posting where he could fly. He was a good pilot and he liked leading in the air. The best assignments of his career had been commanding a Hurricane squadron during the Battle of Britain and then the Kenley Wing later in the war. There were no positions like that in peacetime, of course, but there were still flying jobs to be had. Maybe, if the RAF was unwilling to let him fly, he should throw in the towel and try to get employment in civil aviation. Except that he was a fighter pilot, an erstwhile aerobatics pilot, and he didn’t have the qualifications on heavy, multi-engine aircraft that the airlines wanted. Not to mention that there were tens of thousands of ex-RAF pilots from Bomber, Transport and Coastal Commands, who did have those qualifications. There was no point in chasing fantasies. He was not going to get a flying job anywhere in the UK.

Some of his former colleagues had found work with the air forces in the colonies — South Africa, Kenya, India, Burma, Malaya. Sometimes memories of Singapore haunted him with alluring images of the tropics and sailing on the South China Sea. But he had no friends or relatives in influential positions in those distant places. What was he supposed to do? Spend his last shilling to go to the ends of the earth and then — find nothing? Even if he hadn’t been married, he would not have risked it.

To readers familiar with Where Eagles Never Flew, Robin Priestman is no stranger. In the earlier novel, which describes the Battle of Britain, Robin is shot-down and wounded fighting in France and then serves as an instructor at an Operational Training Unit before being entrusted with command of a front-line squadron facing the Germans in the late summer of 1940. Cold Peace picks up his story two-and-a-half years after the end of the war, or seven years after the close of Where Eagles Never Flew. In the meantime, Robin has gone to staff college, served on Malta, commanded a fighter wing, and spent almost 18 months in a German POW camp. Since the end of the war, he has flown only a desk -- a "mahagony Spitfire" as they sometimes called it -- in a staff job in London.

All that has not left him unchanged. Particularly his time as a POW has left scars -- not the least of which is an intense dislike of Germans. The thought of being sent to Germany in a position where he will be expected to be nice to Germans does not exactly please him. But his options are very limited. Britain is in debt. The Labour government is cutting back on the military. Jobs are scarce and officers who say "no" to assignments unwanted. So Robin is off to the former Luftwaffe training airfield Gatow, which has the reputation of being a sleepy backwater of no particular importance to anyone.

Robin's initial problem is that he doesn't really have a clue what the RAF is doing there. The Germans are docile, so there's no need for the occupation forces to use military means to keep them in line. The Russians on the other hand have a 100:1 superiority in fighter aircraft in theater -- which makes Robin's lone Spitfire squadron useless in a fight with the Russians. It is only as the Soviets gradually tighten the screws that Robin comes to understand his role -- and how vital it is for the future of Europe.

Excerpt 2:

With his courtesy calls on the British Commandant and Air Commodore Waite scheduled for the afternoon, Priestman had a few hours to prepare. Given that he’d seen nothing whatsoever of Berlin, he asked Squadron Leader “Danny” Daniels, commander of the lone Spitfire squadron stationed at Gatow, to give him an aerial tour of Berlin.

Priestman had a secondary motive for this request: he wanted to fly a Spitfire again. The last time he’d been at the controls of a Spit, he’d been bested in a dogfight and ended up a prisoner of war for seventeen months. On his return from internment, he’d requalified as a pilot at an RAF Operational Training Unit, but it had been outfitted with Typhoons and Mustangs. Since then, his only flying had been weekend flips on an Anson at Northolt to retain his flying status. He knew he had to erase that last flight into humiliation and captivity with a successful flight on a Spitfire. It wasn’t that he expected major problems, but he wanted to get this encounter over with as soon as possible so he’d be free to move on.

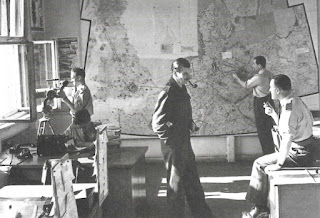

Priestman pulled his Irving flying jacket over his uniform and swapped his shoes for flying boots in his office, then with his gloves stuffed in the pockets, he crossed over to the squadron dispersal hut, where Danny awaited him. The Squadron Leader indicated two Spitfires that had already been checked and fuelled by the ground crew.

As they walked side-by-side toward the aircraft, Danny remarked. “I can’t tell you what a pleasure it is to have you here, sir. I know the chaps would like a chance to talk to you in more depth, and I was wondering if you could find the time to talk to the squadron one of these days.”

“About what?” Priestman asked warily. He had spent years trying to shake off the reputation of an irresponsible aerobatics pilot and playboy. That image had been replaced by “Battle of Britain ace.” Proud as he was to have taken an active part in the defence of the realm in 1940, that had been almost eight years ago. He was now thirty-two and he didn’t want his greatest glory to be what he’d done at twenty-four. He wanted to have a meaningful future, not just a glorious past.

“Oh, just your wartime experiences, sir,” Danny confirmed his fears and Priestman was on the brink of declining when he added, “You won’t remember me, but I briefly served in your wing before you were shot down over France.”

Irritation was instantly replaced with mortification. Priestman had not recognized the Squadron Leader and apologised at once. “I’m sorry, Danny. I didn’t recognise you.”

“No reason why you should, sir. I was straight out of flight school and a pilot officer in 148 Squadron, sir. The sweep on which you were lost would have been my third operational sortie, but my oxygen went u/s and I had to abort.”

“Just as well. We ran into what felt like the whole bloody Luftwaffe — or anyway, all the FW190s they had.” Priestman had seen at least two other Spitfires flame out in the dogfight that had taken him out of the war.

“Yes, I was a bit shaken when four of you didn’t return, and the others were badly shocked that you were one of the missing. Although I missed the op, I took part in the efforts to find you.”

Priestman looked at him blankly.

“We flew three different sweeps to find your Spitfire and try to determine if there was any chance you’d survived the crash. No one remembered seeing any parachute, you see.”

“I’m honoured. I didn’t know that. I hope no one was lost trying to find me.”

There was just a hint of hesitation before Danny answered, “Not that I can remember, sir.” Priestman concluded that either Danny really couldn’t remember, or else someone had been killed and the Squadron Leader kindly chose not to tell him.

No comments:

Post a Comment