Description is the mortar that holds a book together.

Without it characters would exist in an empty, featureless world and action would take place in black hole. The best plot and the most appealing characters can be lost in bad descriptions -- or the complete absence of them.

Before an author can describe anything, of course, they have to be able to picture it themselves! So the first step to getting a description right is learning about the environment of the novel. That is one of the reasons I make an effort to visit the principle venues of my books -- from Jerusalem to Sparta.

Yet while travel is good for getting the physical environment right -- the climate, the vegetation, the landscape etc., many components necessary for setting the stage of a novel are ephemeral and transient. This is most obvious in the case of novels set in the distant past where everything from the domestic architecture to the clothes and music have been lost. Yet, to a lesser extent, it is true even when writing about the more recent past.

The Second World War may not seen all that long ago (at least to those in my generation), yet a tremendous amount has changed since it ended. Fortunately, one of my test readers is older than I am and tipped me off that I had not succeeded in capturing the atmosphere of wartime Britain in my first draft. I went back and did more research. This entailed reading diaries, memoirs, letters and good social history stuffed with examples, photos, and statistics.

Once immersed in an era and comfortable with what I want to describe, the challenge becomes highlighting those aspects of a scene that can help the reader visualize the world of the novel -- without boring him. As always, getting the facts straight is not enough to evoke an image for the reader. Indeed, a meticulous listing of essential facts is far more likely to bore the reader and make their eyes cross than help them to see something. Here's what I mean.

I could say:

The Lancaster was a 69 feet 4 inches long, 20 feet 6 inches high and had a wingspan of 102 feet for a wing area of 1,297 feet. It weighed 36,900 lbs and could carry a bomb load of 12,000 lbs without modification. It had four Rolls-Royce Merlin engines with 1,280 hp each.

or

The Lancaster sat

nose-in-the-air with its double-finned tail low to the ground and its

hundred-feet wingspan stretching grandly to either side. The fighters were toys compared to

this. Kit liked to think of the Lancaster as a four-horse chariot from which

they hurled death like a modern-day Hector battling the arrogant, invading

Achilles.

Or here's another example.

The aircraft took off after dark. All were painted a mat-black and the flare path was dim so it was hard to see. The Lancasters lined up on the taxiway, then turned one after another onto the runway. Kit stood with the other spectators and watched. When an aircraft was cleared for take-off, the caravan beside the runway flashed a green light. The aircraft at the head accelerated, passed the crowd of people watching, and gained speed until it had sufficient lift for take off. Once airborne, it climbed slowly because they were very heavy.

Or:

A-Able turned onto the runway. The rotating blades of the

four propellers caught the light from the flare path and formed ethereal silver

disks in the darkness. Otherwise, the aircraft blended into the night. Painted

a mat black, the hulking dark shape hung suspended between a pair of

navigation lights, one on the tip of each nearly invisible wing. A tiny

greenhouse lit by eerie bluish lights floated above yet astride the barely

perceptible fuselage. Inside this tiny glass structure, dark shapes moved.

To Kit's left a green light appeared. The earth beneath his

feet started to vibrate as the engines changed their tone from a low growl to a

high-pitched roar. The black thing started rolling towards them; the eerie

lighting grew larger and the shapes inside became human heads.

The massive machine rushed toward the cluster of spectators,

gaining speed. Then the great

winged monster whisked past and raced away into the darkness stretching to the

left. The glass bubble of the mid-upper turret crouched upon its long, black

back like a jockey on a massive charger. The flare path lights flashed off the

Perspex of the rear turret.

A-Able’s nose lifted and seemed to drag the great bulk of the

aircraft after it. It hung faintly silhouetted against the night sky. The

wheels folded into the body, like a bird tucking in its feet. Abruptly the

navigation lights darkened. The next aircraft, U-Uncle, turned onto the head of

the runway.

Finally, a last example of a more domestic setting:

The WAAF officer was five feet four tall and weighed 120 lbs. She was 26 years old. She had dark eyes and hair, which she wore rolled into a hair net to keep it off her neck. She wore red lipstick and nail polish, although neither was allowed in the WAAF.

or:

A moment later a WAAF officer walked into the

parlour, tearing off her cap and hair net in a single motion. She shook her head

to let her long dark hair fall lose. Georgina confronted a strikingly beautiful

young woman with a full but graceful figure and straight dark eyebrows over

large, dark eyes. Her lipstick was perfect, and her nail polish red. Georgina

thought she’d heard that WAAF weren’t supposed to wear either, but as this

young woman came across the room with her hand extended, Georgina sensed she

was the kind of woman used to privileges.

Next week I will explore the challenge of dialogue in a unique culture -- the RAF.

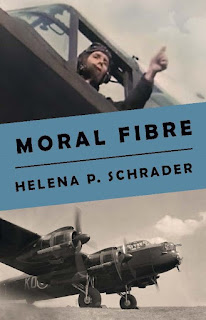

Riding the icy, moonlit sky— They took the war to Hitler.

Their chances of survival were

less than fifty percent. Their average age was 21.

This is the story of just one Lancaster

skipper, his crew,and the woman he loved.

It is intended as a tribute to

them all.

Order Now!

Flying

Officer Kit Moran has earned his pilot’s wings, but the greatest challenges

still lie ahead: crewing up and returning to operations. Things aren’t made

easier by the fact that while still a flight engineer, he was posted LMF

(Lacking in Moral Fibre) for refusing to fly after a raid on Berlin that killed

his best friend and skipper. Nor does it help that he is in love with his dead

friend’s fiancé, who is not yet ready to become romantically involved again.