Creating credible female characters in a historical setting where they do not enjoy the same freedoms and status as women of the present can be a challenge. Based on the historical fiction I have read, many authors "solve" the problem simply by making their heroines "unusual" or "ahead of their time." That is, making them modern women and explaining them away as "exceptional" because of some circumstance in their childhood. (Usually a mother who died in childbed, no brothers and an indulgent father.) While that approach is easy, it generally detracts from the authenticity of a novel. I've found that making a greater effort to make women conform to their own age is far more rewarding.

The key — as with most things in historical fiction — is understanding the period you are writing about. In depth research, particularly reading first-hand accounts by women of the period or biographies of women from the period, will usually enable a writer to start seeing the world through the eyes of women of the period. This is critical because to write credible characters, male or female, one must not depict them with thoughts, feelings and ambitions dictated by our modern understanding of what is right and wrong, but rather with their own values and expectations.

Research will aid the author in two ways:

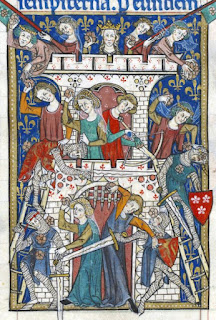

First, much of what we think we know about a period of history may be hearsay, oversimplifications, propaganda or based on discredited sources. An excellent example of this is the common misperception that women in the Middle Ages were “mere chattels.” This is utter nonsense easily disproved by any serious (or even fairly superficial) research into the legal status, economic role and biographies of women of the period. Women could be sovereigns, lords, guild masters, and independent businesswomen. They took oaths of fealty, commanded men, inherited and controlled wealth including land, had professional training, were literate and numerate and engaged in professions such as medicine. In short, a novelist writing about women in the Middle Ages might not find them so different from modern women as she thinks before doing her research.

Second, however, in depth and particularly biographical research should enable a novelist to start to identify with and empathize with her female characters even in those areas and on those topics where their attitudes, values and expectations do differ more radically from our own. There is no question, for example, that women in WWII with very few exceptions were paid far less than their male counterparts and were restricted in their role. There was nothing like equality of opportunity and socially many customs were patronizing. Yet, when reading the memoirs of women in the Second World War the thing that jumped out at me was the enthusiasm and excitement they felt to be doing so much. While we look at their roles like the pessimist, seeing only what they did not have, they almost universally looked on their new empowerment like the optimist, seeing what they did have.

Likewise, the heroines of my WWII novels are far from “liberated” or powerful, but they don’t spend their time bemoaning their fate either, preferring to take the opportunities they have and contribute to the great national cause of which they saw themselves a part. Find out more about my WWII novels at: https://www.helenapschrader.com/wwii.html